craft

This week You! talks to Lahore-based artist Ammara Khan, to find out about her meticulously crafted handmade embroideries…

Pakistan is well known all around the globe primarily because of its unique culture and heritage. Our traditions have a distinctive taste especially in hand made embroideries. Pakistani traditional embellished dresses are well recognised and demanded not just within the country but across the world. At first, these embroidered dresses were handmade by our women, who used different fabrics, threads, stones, a variety of yarns with all their heart and efforts to produce a stunning and stylish piece of clothing. Soon with the development of industries, we have machines to do all this and the art of hand embroidery is fast losing its essence.

An artist, whether a designer, is the best mediator who promotes and preserves art and culture. In this regard, You! heads over to Ammara Khan Atelier to find out about her meticulously crafted hand embroidered collection. The Lahore-based designer, talks about how from a very young age she was interested in art preservation, wanting to revive or reconstruct intricate work. “Ever since I was a very little girl, I had a passion for design and had a unique sense of styling my clothes put together from my brother’s closet. Although, I came from a family where my mother was a doctor and my older siblings were studying to be doctors; yet, I was tilting towards arts early on. My mother used to drag me to antique shops and markets in Pakistan, London and America,” she shares.

Ammara and her mom used to go to thrift stores where her mother would be smitten by carpets, old furniture pieces, Swati embroideries and traditional crafts. While reminiscing about her childhood Ammara tells, “My khala had a passion for Pakistani handicrafts. She was someone who played a pivotal role in the establishment of ‘Behbud’. I used to attend the exhibitions and discover the age old Sindhi ralli and shadow work. I used to cherish those handwork details thereon I developed the passion for art and crafts; and vowed to be able to revive the crafts that are unbelievably dying at a rapid pace.”

She made it to the prestigious FIT Fashion Institute of Technology, New York and Polimoda based in Florence which is Italy’s number 1 fashion school. “What I learnt at both of these institutes was very different to what I am doing here in Pakistan. After getting my degree I came back to Pakistan to set up my own work studio but I found a new change of dynamics here. There was a completely new world of embroidery and embellishment that I knew nothing of. I was a young student willing to learn and by some miracle, I was led to these incredible craftsmen through my mother who I consider my ustads.”

In those years, Ammara was taught the technique of salma, art of needlework and aari work. It was the beginning of Khan’s learning who was able to learn and experiment putting attention to detailing.

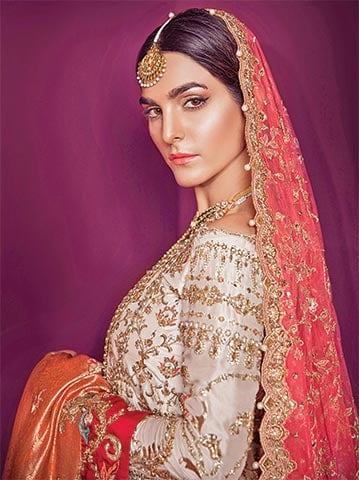

Impeccably finished embellishments with miniature embroidery in fine silk threads make all her couture pieces one of a kind. The extreme fine nature of the material and the meticulous hand embroidered craftsmanship involved makes each signature piece a keepsake for generations. It is refreshing to see hand embroidery come to the forefront as this kind of art form is dying. Her biggest triumph has to be her complete authority in cuts and excellent use of fabric with emphasis on handwork.

“I have felt that ever since I started off in 2002, my love for craft has only increased. Each time I do embroidery, I want to develop this further by adding something to it or by taking the age old technique and making it modern and relevant for today. I used to sit around craftsmen for hours observing every single stitch involved in embroideries. It’s a continuous process of learning and making them relevant to my designs as of now,” expresses Ammara.

So, what makes Ammara Khan’s work unique is the contemporary silhouette and modern colour palettes juxtaposed with the old handwork techniques. She explains on how she has employed the technique of baadla which uses the mukaish ki dorri (flat metallic strip very thinly cut) with a design drawn on the paper which you first cut it out by hand then you stick the card board paper on the fabric and stitch the mukaish over that. “This is a specialised technique that very few people are doing now and there are very few karighars who can do it. Baadla is very similar to wasli type of embroidery which is tilla based,” she explains.

“We do very fine zardozi, single resham, tikka kaam, French knot, machli tanka, taarkashi and gotta work. I have realised that my new team of karighars are not truly aware of gotta work and sometimes I have to teach them because they don’t know the real craft. The senior team of workers is however, more familiar with these techniques yet a decade ago there was value and appreciation for this craft,” she laments.

However, now with mechanisation women are expecting things to happen very quickly. “People are not willing to pay the price for this craft. The multi head machine embroidery base gives off the same affect then why would you dole out more money?” she questions. But people who are connoisseurs of real fashion will never go for the short cut or a quick version. “There are pieces that you can pull out of your closet which won’t date or look outdated. Timeless pieces and real crafts go together but sadly design houses nowadays are focusing less on generating fine craft and more on producing synthetic pieces,” she informs.

Highlighting the overdose of machine work inspired garments she says, “We have gone far too much in multi head machine. All the clothes started to look generic-the same.

“When there is no demand or value left for hand work; the karighar’s source of income will get affected and they will not learn the skills. Like for a young shagird or an apprentice you need to learn the craft at a work shop. Now, the child labour laws are also strict than they were in olden times. These children are now attracted to earn money by working at a mobile shop to sustain their livelihood rather than spending hours learning the craft which has no scope.”

It is sad that people have opted out of it to go for quicker money making solutions. We are losing a whole generation of karighars so the only plausible solution is if there are design houses willing to revive the craft and hold on to it or if they ensure that their design ateliers will have 75 per cent handwork.

The bespoke chaadar from Ammara Khan’s new collection ‘Dareynoor’ is a piece of art which took about two years to complete. “I had to dedicate eight workers but it is something that I want to gift to a museum. It was never made for commercial purpose of selling but it’s a masterpiece.” Anyone who understands heritage, couture, fashion sensibilities and above all art are the people that the designer creates designs for. People who value heirlooms and bespoke creations, people who admire her strength of dedicating endless hours sitting over addawallahs using old techniques and people who really value her work and want to see the details real up close. Most importantly those, who vie for quality of product and design over price points. “My heritage is very close to my heart it’s what I’ve seen growing up and the clothes and traditions I have lived in. I commend people who understand the intricacies and support artistry of couture and give me the freedom of creating for them. However, these are far and between,” Khan ends on a thoughtful note.